The Pikes Peak International Hill Climb is unique in many ways. One thing that makes the most famous hill climb in the world so special is the heavy limit on test drives. Volkswagen Motorsport wasn’t able to complete hundreds of laps during the development of the I.D. R Pikes Peak, like Formula 1 teams can do on certain racetracks, for example. Before driver Romain Dumas reached the 4,302-metre summit in a new record time, he wasn’t even able to complete one full test run of the actual track with Volkswagen’s first all-electric powered racing car.

“We relied heavily on computer simulations in particular in the initial phase of development of the I.D. R Pikes Peak,” explained Dr. Benjamin Ahrenholz, head of calculation/simulation at Volkswagen Motorsport.

The team used computer technologies in multiple areas

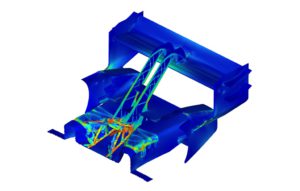

“We used simulation programmes to calculate the components of the I.D.R Pikes Peak facing heavy structural wear and tear, for example, the chassis, monocoque, rear subframe and rear wing,” said Ahrenholz.

The aim of the computer-aided engineering (CAE) was always the same: a component should be as light as possible. But it had to easily master the pressures that occur during the race. The team performed relevant simulations using the finite element method (FEM). During that method, the extremely complex structure of the components of the racing car was split up into a multitude of small components with predictable behaviour – the finite elements.

Computer designs optimised components

“This enabled us to simulate which components of the I.D. R Pikes Peak might need to be strengthened, where we could conserve material and thereby weight, or where the construction might need to be changed,” described Ahrenholz. When necessary the computer used topology optimisation to make suggestions for an improved design.

The fact that the 19.99-kilometre track already largely existed as a computer model helped Dr. Benjamin Ahrenholz’s team. The upper section of the track, in particular, posed challenges for the Volkswagen Motorsport engineers. “The road surface there is so uneven that the load on the chassis is much greater than on the extremely level strip of the lower section of the racetrack,” said Ahrenholz. “We weren’t entirely sure what would await the I.D. R Pikes Peak in the upper section beforehand, which is why we factored in a certain safety margin.” The CAE procedure also enables not pushing individual components to the limit, with a few mouse clicks, but definitely time-consuming recalculations.

Hundreds of aerodynamic configurations tested on the computer

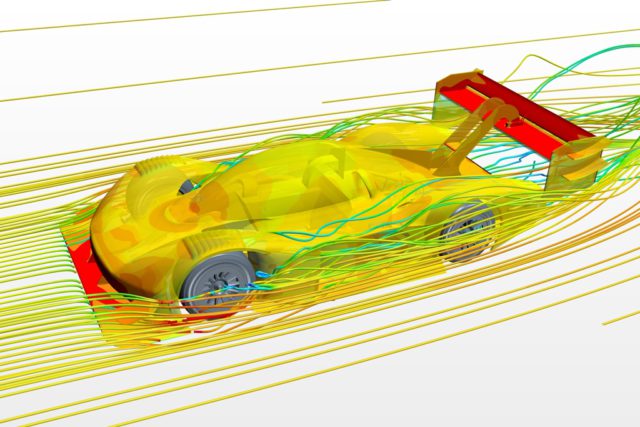

Another computer-based technology was used during the development of the aerodynamics for the I.D. R Pikes Peak, computational fluid dynamics (CFD, part of computer-aided engineering). The computer programme calculated how even the smallest modifications to the body and the spoilers of the I.D. R Pikes Peak affected the drag coefficient, downthrust or the inflow of coolers. “In this way, we simulated hundreds of different configurations before we tested a 1:2 model in the wind tunnel,” reflected Ahrenholz.

The moment when the I.D. R Pikes Peak rolled out of the paddock for the first test drive on the actual racetrack in the US state of Colorado was exciting for the head of the simulation/calculation department at Volkswagen Motorsport and his team. “A degree of uncertainty always remains when a racing car has been completely redesigned,” said Ahrenholz.

It’s #ThrowbackThursday! Today we are having a rewind and a look back on the #PikesPeak practice runs. Here’s the unfiltered, uncut and unedited speed of our very own @RomainDumas and the @Volkswagen I.D. R Pikes Peak. Not a believer yet? Watch this!#ProperCharge #EV #1stOf3 pic.twitter.com/EtlrrB4fVr

— VolkswagenMotorsport (@volkswagenms) July 26, 2018